9-minute read

keywords: entomology, ethology, neurobiology

It is tough being a social insect. When people are not trying to exterminate you, they might marvel at the collectives you form, but does anybody think much of you, the individual? Leave it to Lars Chittka, a professor in sensory and behavioural ecology, to change your views. The Mind of a Bee is a richly illustrated, information-dense book that explores a large body of scientific research, both old and new. Chittka’s book was followed not a year later by Stephen Buchmann’s What a Bee Knows. This, then, is the first of a two-part dive into the tiny brains of bees and the remarkably advanced behaviours that they show.

The Mind of a Bee, written by Lars Chittka, published by Princeton University Press in June 2022 (hardback, 260 pages)

Chittka is very focused in his approach and The Mind of a Bee effectively summarizes a large number of experimental studies in narrative form, with very few diversions. He cleverly avoids overheating your brain by having chapters flow logically into each other, but especially by dividing each chapter into short, headed sections. Each of these takes a particular question and discusses a few relevant studies in anywhere from one-half to three pages. Some of these are his own work but he ranges far and wide and includes both classic and recent research. The book is furthermore illustrated with numerous diagrams and photos that helpfully clarify experimental protocols and results. Honey bees are unsurprisingly the most intensively studied (as if to emphasize that point, Princeton released the new reference work Honey Bee Biology just last month) but Chittka discusses informative studies across a range of bee species and sometimes other insects as well. The book roughly covers three biological disciplines: sensory and neurobiology, ethology, and psychology.

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Many flowers sport UV patterns invisible to us. Remarkably, UV photoreceptors are found in numerous insects and other crustaceans whose shared ancestry goes back to the Cambrian, predating the evolution of flowers in the Cretaceous by hundreds of millions of years. In other words, it seems flowers adapted to insect colour vision rather than the other way around. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarized light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Interestingly, some sensors are multipurpose, such as the cells that respond to both touch and electric fields. How do bees tell those sensations apart? Much as Ed Yong described in An Immense World, Chittka thinks they possibly do not, “the two types of stimuli […] felt as variations of the same modality” (p. 47).

Justifiably, the book opens with sensory biology. Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism, Chittka argues, we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered. These are shaped by both evolutionary history and daily life (i.e. what information matters on a day-to-day basis and what can be safely ignored). Chapter 2 deals with the historical research that showed that bees do have colour vision and furthermore can perceive ultraviolet (UV) light. Many flowers sport UV patterns invisible to us. Remarkably, UV photoreceptors are found in numerous insects and other crustaceans whose shared ancestry goes back to the Cambrian, predating the evolution of flowers in the Cretaceous by hundreds of millions of years. In other words, it seems flowers adapted to insect colour vision rather than the other way around. Chapter 3 bundles together research on numerous other senses, including ones familiar (smell, taste, and hearing) and unfamiliar to us (perception of polarized light, Earth’s magnetic field, and electric fields). The antennae of bees, in particular, are marvels; Chittka likens them to a biological Swiss army knife, packing numerous different sense organs into two small appendages. Interestingly, some sensors are multipurpose, such as the cells that respond to both touch and electric fields. How do bees tell those sensations apart? Much as Ed Yong described in An Immense World, Chittka thinks they possibly do not, “the two types of stimuli […] felt as variations of the same modality” (p. 47).

“Before we understand what is in the mind of any organism […] we first need to understand the gateways, the sense organs, through which information from the outside world is filtered.”

Tightly connected to sensory biology is how this incoming information is processed in the brain, though Chittka postpones discussing neurobiology to chapter 9. He describes the discovery and function of different brain areas and highlights the work of Frederick Kenyon who would inspire the better-remembered Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Thanks to them, we now understand that brains consist of numerous specialised nerve cells. Though the bee brain is small, Chittka argues that size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring of neurons that matters. However, his most pithy statement on this idea is not made in this book, but in conversation with Justin Gregg in If Nietzsche Were a Narwhal: “In bigger brains we often don’t find more complexity, just an endless repetition of the same neural circuits over and over” (p. 167 therein). Indeed, modelling work with artificial neural networks shows that a small number of cells can already tell apart complex visual patterns. Rather than be surprised that small-brained insects such as bees can do so many clever things, Chittka instead tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?” (p. 153).

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers to other worker bees. What I did not know is that they also use it in another context. Before a swarm moves to a new home, workers use that same waggle dance to tell others about the location of potential nest sites during a days-long process of building a consensus on where to relocate to. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. Interestingly, as he highlights, some behaviours such as dead reckoning (the ability to return home in a straight line after a meandering foraging trip) are shared with other Hymenoptera such as Cataglyphis desert ants. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50).

What clever things do bees do, you ask? That is the subject of the preceding five chapters where Chittka surveys a large body of behavioural research. Honey bees are famous for their waggle dance by which they communicate the location of flowers to other worker bees. What I did not know is that they also use it in another context. Before a swarm moves to a new home, workers use that same waggle dance to tell others about the location of potential nest sites during a days-long process of building a consensus on where to relocate to. But Chittka discusses more, much more: how bees navigate space using landmarks, show a rudimentary form of counting, solve the travelling salesman problem, learn to extract nectar from complex flowers, learn when to exploit certain flowers (and when to ignore them), and learn new tricks by observing other bees. Interestingly, as he highlights, some behaviours such as dead reckoning (the ability to return home in a straight line after a meandering foraging trip) are shared with other Hymenoptera such as Cataglyphis desert ants. But what about instinct, something most behaviours were traditionally ascribed to? He has some insightful comments on this: “even the most elemental behavior routines need to be refined by learning: instinct provides little more than a rough template” (p. 50).

“Chittka argues that [brain] size is a poor predictor of cognitive skills; it is the wiring […] that matters […] [He] tickles the reader with the opposite question: “Why does any animal need as large a brain as a bee’s?“”

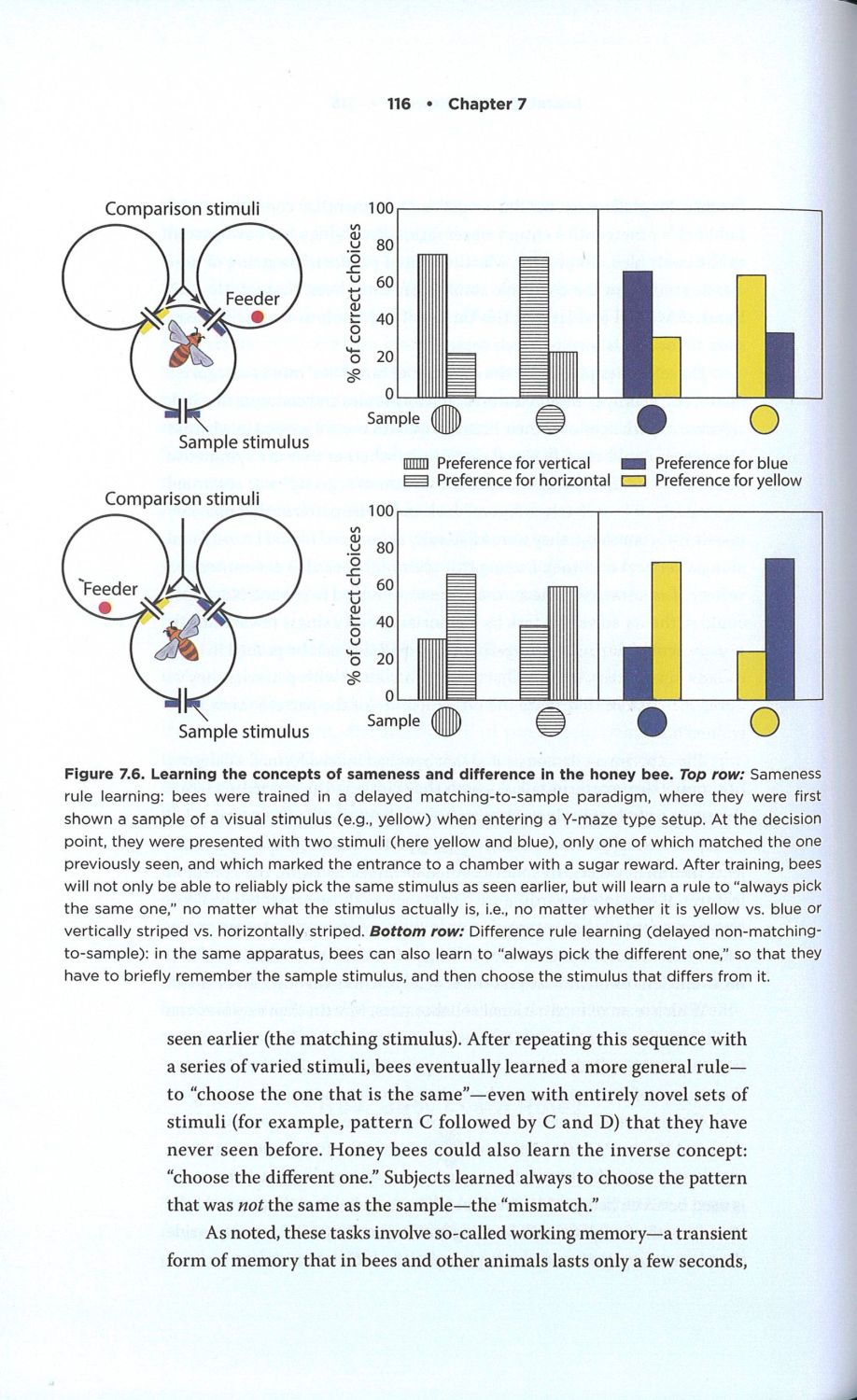

What really made me fall off my chair is that bees have long been outsmarting researchers. Many behavioural experiments take the form of choice tests, where bees need to pick between two locations or objects that differ in e.g. colour or shape with one option containing a sugary solution as a reward. For years, it seemed bees failed at even simple discrimination tasks, simply checking out both options in random order. Turns out this happened because there was no cost to making the wrong choice. Bees just want the reward and when inspecting the different options takes time, “a quicker solution for them was simply to be indiscriminate” (p. 109). When Adrian Dyer, working in Chittka’s lab, modified experimental protocols and added a bitter-tasting solution to the wrong choice as a penalty, bumblebees suddenly became far more discriminating. What this reveals is that, if they could get away with it, bees would trade off accuracy for speed!

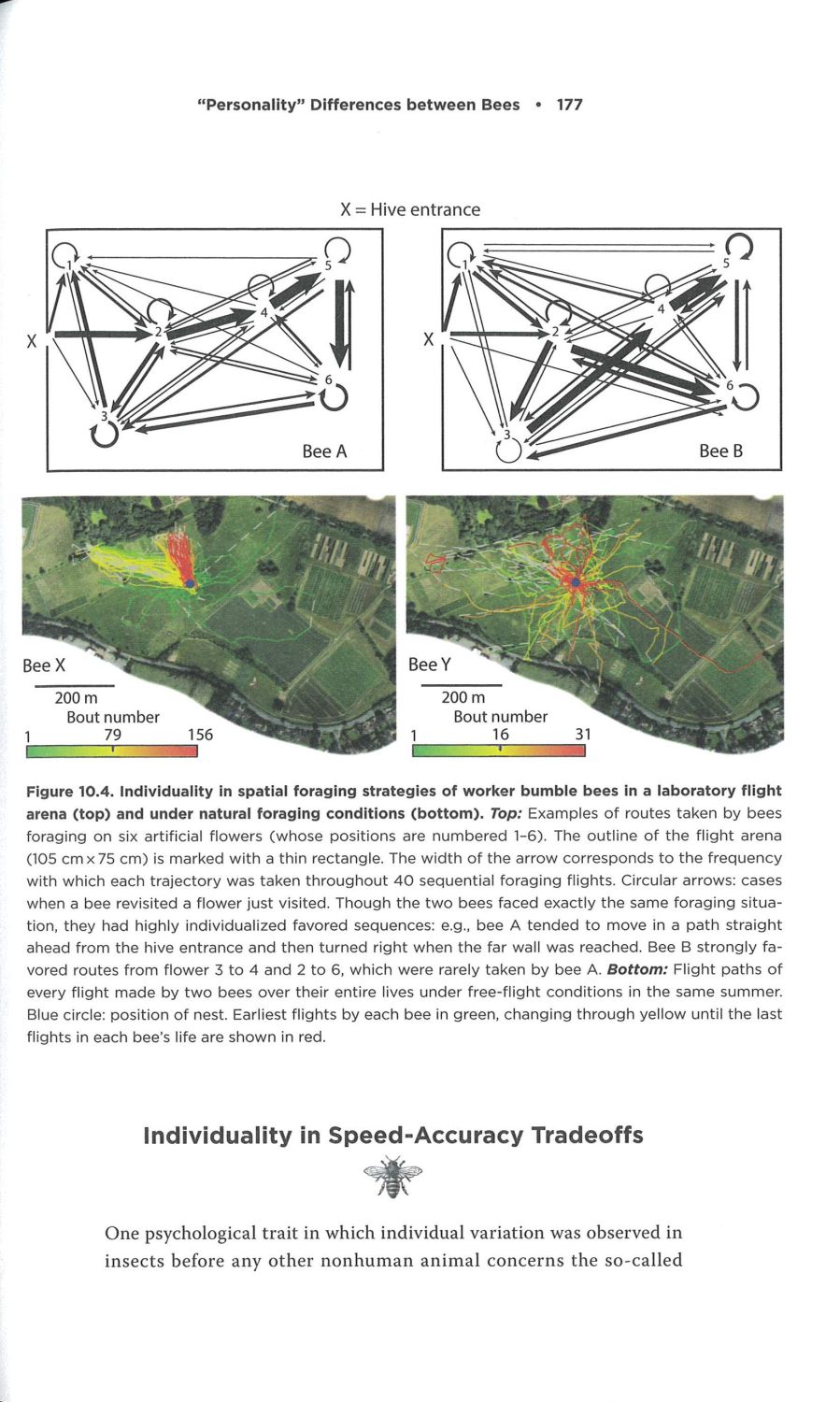

The final two chapters explore bee psychology. One chapter shows how, in a hive full of bees, the members are not anonymous and interchangeable. Rather, they show individual differences in e.g. their preferred order in which to visit flowers during foraging or how fast they learn to solve problems. The final chapter makes the case that bees have a form of consciousness, though Chittka clarifies he is not arguing it is as rich and detailed as that of humans. That said, he discusses research that shows that bees certainly have nociception (a neural response to injuries), likely also have the subjective experience of pain, seek out psychoactive substances (e.g. nicotine that has leached from leaves into flowers), can tell apart self from other, have a self-image (large bees will carefully size up small openings and fly through them sideways if necessary), have an awareness of past and future, and possibly even possess metacognition (the ability to think about their thoughts). In short, they show a slew of behaviours that scientists will label as evidence for consciousness when exhibited by bigger-brained vertebrates. Chittka is happy to play devil’s advocate: sure, theoretically, all the behaviours described in this book could be replicated by an unconscious algorithm. However, the required list of specific instructions is growing long and, increasingly, the more likely answer seems to be that bees possess “a consciousness-based general intelligence system” (p. 208).

The final two chapters explore bee psychology. One chapter shows how, in a hive full of bees, the members are not anonymous and interchangeable. Rather, they show individual differences in e.g. their preferred order in which to visit flowers during foraging or how fast they learn to solve problems. The final chapter makes the case that bees have a form of consciousness, though Chittka clarifies he is not arguing it is as rich and detailed as that of humans. That said, he discusses research that shows that bees certainly have nociception (a neural response to injuries), likely also have the subjective experience of pain, seek out psychoactive substances (e.g. nicotine that has leached from leaves into flowers), can tell apart self from other, have a self-image (large bees will carefully size up small openings and fly through them sideways if necessary), have an awareness of past and future, and possibly even possess metacognition (the ability to think about their thoughts). In short, they show a slew of behaviours that scientists will label as evidence for consciousness when exhibited by bigger-brained vertebrates. Chittka is happy to play devil’s advocate: sure, theoretically, all the behaviours described in this book could be replicated by an unconscious algorithm. However, the required list of specific instructions is growing long and, increasingly, the more likely answer seems to be that bees possess “a consciousness-based general intelligence system” (p. 208).

“Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).”

As mentioned above, this book is focused. If you enjoy reading about the facts and the study system with minimal (autobiographical) diversions, Chittka has got you covered. The only digression he allows himself is to include biographical details of older generations of scientists. This includes inspiring tales such as Karl von Frisch who described the honey bee waggle dance and later barely escaped being dismissed from his post by the nazis, allowing him to train up future generations of bee researchers (Chittka belongs to the third generation). And look out for repeat appearances of Charles Turner, a now largely forgotten African American scientist who published pioneering work despite having been denied a professorship based on his ethnicity. But there are also tragic stories such as Kenyon’s, who, despite his discoveries, was unable to secure a permanent job, snapped under the psychological pressure, and was incarcerated in a lunatic asylum, where he died more than 40 years later, alone and forgotten. Chittka includes occasional quotations from historical literature to show that “many seemingly contemporary ideas about the minds of bees had already been expressed, in some form, over a century ago” (p. 15).

The Mind of a Bee makes for fascinating reading. The book’s tight structure and numerous illustrations make it accessible, though be prepared for an information-dense book. Having now been thoroughly convinced by Chittka that bees are anything but little automatons, what can pollination ecologist Stephen Buchmann add to this one year later? I will turn to What a Bee Knows next to find out.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Even since I’ve read a chapter in a book of R. Powell on insect consciousness, I’ve been eager for her announced book to be published: “Alien Minds: Invertebrate Intelligence and the Evolutionary Meaning of Life”. It’s in progress and co-written with Irina Mikhalevich, but I have no idea when it will be published, her site hasn’t been update in some time, and she should have published a book about genetic engineering in 2022 according to her bio too, and that hasn’t happened either.

Anyhow, it will be interesting to read your next review, and read one of these bee books while waiting.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That sounds like a fascinating title, especially given her previous book that I reviewed : )

LikeLiked by 1 person

yeah, I’m eager to read whatever book she publishes next. I also read/reviewed her book on the biology of ethical progress, a brilliant read too.

LikeLiked by 1 person