8-minute read

keywords: evolutionary biology

This is the second of a two-part review where I am revisiting the idea that evolution by natural selection is not a process that will always result in perfect adaptations. I first touched on this back in 2019 when reviewing Daniel S. Milo’s Good Enough which, as per its title, argued that evolution does not care for perfection: good enough to survive will do just nicely. Having previously reviewed Andy Dobson’s witty Flaws of Nature, I am now turning to Telmo Pievani’s Imperfection: A Natural History which offers an altogether more erudite take on the topic.

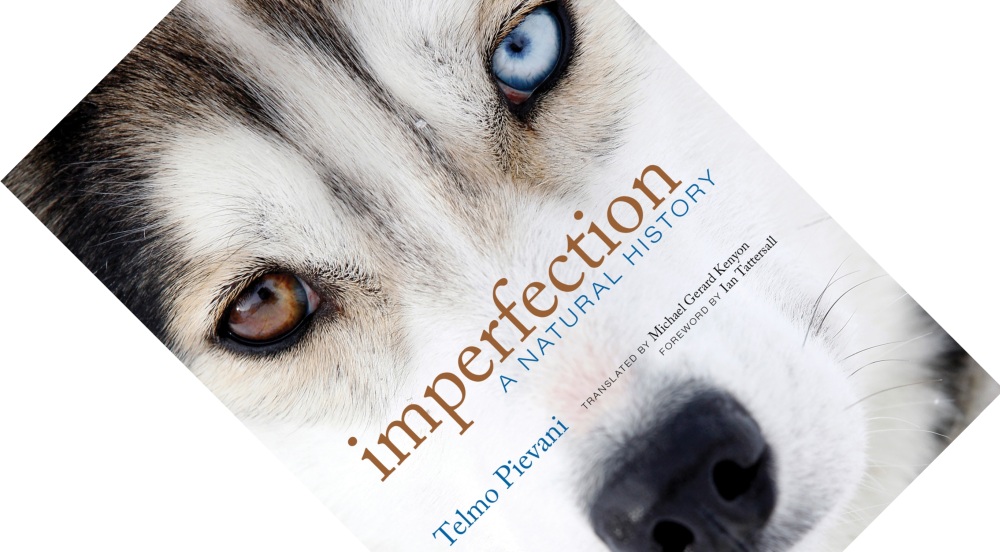

Imperfection: A Natural History, written by Telmo Pievani, published by MIT Press in October 2022 (hardback, 164 pages)

Pievani is an Italian evolutionary biologist and science philosopher, holding a full professorship in the philosophy of biological sciences at the University of Padua. Author of over 30 books in Italian, some of which have been translated into English and other languages, he is also a columnist and essayist for several newspapers and scientific magazines, and an active science communicator. Imperfection was originally published in Italian in 2019 as Imperfezione: Una Storia Naturale by Raffaello Cortina Editore. MIT Press published it in English in 2022, courtesy of the late Michael Gerard Kenyon, a professional translator in the fields of biology and medicine who lived in Italy for nearly four decades. Anthropologist Ian Tattersall provides a brief foreword. This book has been on my radar for some time, and the publication of Flaws of Nature was the push I needed to finally read it.

Whereas Dobson’s book argues that natural selection becomes more interesting by focusing on its flaws, Pievani words it even stronger: “Naturalists wanting to understand how evolution works must look for imperfections, for useless and vestigial traits” (p. 144). After an opening chapter on the cosmological imperfections that allowed there to be a universe in the first place, with matter that ended up concentrated in stars and planets, the remainder of the book focuses on the natural history part. A guiding principle is that hindsight is definitely not 20/20. In a strident section titled “Let’s Kill Hindsight”, Pievani writes that it “makes anomalies seem necessary and complete, and therefore perfect even though they are not” (p. 10), and that “Hindsight is a poison. Let’s get rid of it” (p. 12). Drawing on Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius’s notion of clinamen (turning points that are unpredictable regarding what preceded them and decisive for what is to follow), he reasons that evolution can be better understood by looking for such critical junctures and the countless alternatives that could have been.

“The beauty of […] constraints is that, rather than posing a problem for the theory of evolution, they provide “confirmation of the universal common descent of all living beings“.”

In seven chapters and a mere 150 pages, Imperfection is a quick, slick, yet erudite read that posits six laws of imperfection, with some of these ideas later also mentioned by Dobson.

1) Contingencies: Chance events such as genetic drift or a rapidly shifting climate can modify the rules of the game, changing traits from beneficial to burdensome. The Irish elk with its giant antlers had the energetically costly strategy of regrowing them every year. This is permissible in a stable environment but may well have become prohibitive during the rapid climatic changes at the end of the last Ice Age. Pievani adds a few caveats to be mindful of: “In the incessant tug-of-war between laws and chance, contingency can manifest itself to different degrees” (p. 8). Furthermore, “imperfection and contingency do not imply a supreme and unrepeatable improbability” (p. 14); sequences of historical events are not necessarily unique or somehow special.

2) Compromises: Traits often cannot attain perfection due to trade-offs between different selective pressures. Many sexually selected traits strike a compromise between survival and sex appeal. The peacock’s tail is a frequently cited example but Flaws of Nature discussed others, such as swordtail fish and stalk-eyed flies. Pievani puts it nicely: “Evolution represents an ongoing dilemma” (p. 43).

3) Constraints: Historical, physical, structural, and developmental constraints can all limit by how much traits can evolve. Since evolution cannot go back to the drawing board and start from scratch, we end up with e.g. the sinuses in our face having their drainage openings at the top rather than the bottom, leading to them constantly clogging with mucus. This configuration made sense for our quadrupedal ancestors, but not for bipedal primates. The beauty of these constraints is that, rather than posing a problem for the theory of evolution, they provide “confirmation of the universal common descent of all living beings” (p. 54).

4) Repurposing: Evolution’s tendency to repurpose existing traits means that imperfect structures are actually common. Also known as exaptations, this one was discussed at length in Some Assembly Required. Stephen Jay Gould wrote about the panda’s second thumb (a repurposing of the sesamoid bone in its hand) that it uses while feeding on bamboo. Pievani pithily concludes that “Nature does not make plans, it finds solutions” (pp. 61–62).

5) Excess: Pievani dedicates a whole chapter to junk DNA, what it does, and whether the concept has run its course. Introduced elements and gene duplications provide excess material that can mutate without much risk, and possibly acquire a useful new function in the process. An example discussed here is the protein osteocrin which is expressed in the bones of mice and plays a role in neocortex development in primates. Pievani summarizes this law thusly: “excess, if it can be tolerated, is a source of change because evolution involves the transformation of the possible” (p. 82).

6) Inertia: When environments change faster than organisms can, they start running behind and become imperfectly adapted. Humans, in particular, are starkly maladapted to the modern world they have created for themselves. Pievani concludes that “evolution is a constant struggle between the available material […] and the ever-changing environment around us” (p. 118). For “environment” you can also read “another organism”, resulting in the famous Red Queen hypothesis coined in 1973 by Leigh Van Valen which explains arms races in nature, whether between predators and prey, parasites and hosts, or plants and pollinators. Dobson discussed these as well in Flaws of Nature, adding the insight that selection pressures in such arms races are often unequal, meaning that one side always has the evolutionary advantage.

“Evolution’s tendency to repurpose existing traits means that imperfect structures are actually common. […] “Nature does not make plans, it finds solutions“.”

The presentation of these six laws uses quite a lot of examples from human biology (I recognized many from reviewing Human Errors). Our DNA and brains both resemble Rube Goldberg Machines that are so “unnecessarily complicated [that] neither would pass an engineering test” (p. 98). Pievani also discusses our many bodily imperfections and our numerous mental foibles that give rise to cognitive errors, biases, prejudices, sensory illusions, superstitions, etc.

Given Pievani’s particular interest in the philosophy of evolutionary biology, his writing betrays a well-educated background. He regularly quotes from works by other scholars, including (understandably) fellow Italians such as the aforementioned Lucretius, chemist Primo Levi, neurobiologist and senator Rita Levi-Montalcini, and geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, but also evolutionary biologists such as Stephen Jay Gould and Theodosius Dobzhansky, and philosophers such as Michel de Montaigne, Bertrand Russell, and Peter Godfrey-Smith. Pievani also frequently returns to Darwin’s writings. He struggled to reconcile the fact that “nature is full of leftovers” (p. 47) with his reading of natural theology texts and the critics who objected that his theory failed to explain complex structures such as the human eye. Something I did not know was that his supporter Ernst Haeckel even suggested the term dysteleology for the study of nature’s many imperfections. And yet, despite all this high-brow source material, Imperfection remains incredibly readable with Pievani’s experience in science communication shining through. The chapters are helpfully divided into intriguingly titled subsections. This is one of those books that is hard to put down and full of well-formulated and insightful ideas.

By addressing evolutionary imperfections from different sides, Imperfection feels more full-bodied than Flaws of Nature, even as that book added its share of interesting observations not made here. As such, it is a very nice follow-up if you started simple and want to go deeper. Those with a background in evolutionary biology or an interest in the history of science should not be afraid to jump straight in at the proverbial deep end. This is the first of Pievani’s books that I have read and, for me, establishes him as a notable thinker and writer whose other works I will look out for. For this, however, I will have to continue to rely on the commendable work of publishers such as MIT Press who carefully select and translate the best non-English scientific literature for the monoglot masses.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Dawkins’ Blind Watchmaker have touched on this a bit, but it’s been nearly twenty ears since I read it so I can’t say that with utter assurance. Two examples I remember were the optic nerve punching through our retinas, and of course — the giraffe’s nervous system, which routes one nerve all the way up the neck and all the way down the neck without having anything to do with the head at all.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, both are some of the many examples that feature in this book.

LikeLike