5-minute read

keywords: evolutionary biology

Jules Howard is no stranger to sex. A science writer and zoological correspondent, his gleefully amusing 2014 book Sex on Earth is particularly relevant to the topic at hand. Even there, however, eggs were just a sideshow. And therein lies the problem. Likely, the first question to be asked when eggs come up in conversation is how you like them for breakfast, or some hackneyed joke involving chickens. Focusing on the oology in zoology, Infinite Life retells the history of life, this time from the perspective of the almighty egg.

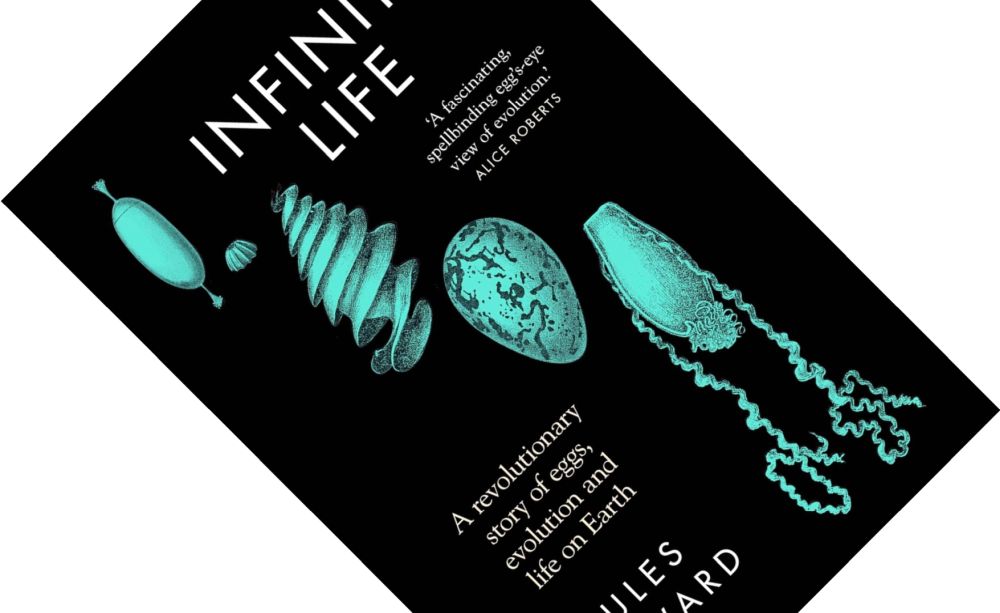

Infinite Life: A Revolutionary Story of Eggs, Evolution and Life on Earth, written by Jules Howard, published in Europe by Elliott & Thompson in May 2024 (hardback, 258 pages)

Howard’s approach in Infinite Life is to take the reader chronologically through the history of life, one geological period per chapter. Familiar as that framework might be for readers of popular evolutionary history books, it is the subject matter that is engrossing; eggs really have been a neglected topic so far. Consider, for example, that though we think of eggs as an animal invention, there have been egg-like precursors. Sometime between 1 to 2 billion years ago, cyanobacteria evolved a resting stage, “an armoured sleepsuit” (p. 9), known as cysts. These acted as “a device that propelled genetic material forwards in time” and you could say that here, in the Proterozoic Eon, “the egg—as a concept—was forged” (p. 12). It was only later, when the earliest animals started experimenting with sex during the Ediacaran, that the first true eggs—”vehicles for genetic mixing” (p. 22)—show up in the fossil record. It needs to be said that the evidence is confusing, fragmentary, and of poor quality, and not accepted by all palaeontologists.

Once the egg was established, Howard takes the opportunity to revisit several critical junctures in evolutionary history. In the Cambrian, for instance, a division took place between organisms with and without separate cell lines. Cnidaria, of which jellyfish are a member, belong to the latter group and produce eggs later in life by dedifferentiating body cells, effectively putting their developmental programme in reverse. Most other organisms you are familiar with (mammals included) at a very early stage of embryonic development split into germ cells (which exclusively produce sperm and eggs) and somatic cells (which go on to form the rest of the body). And this is just one of three important egg inventions during the Cambrian he discusses. Howard proposes several later critical junctures where eggs may have been an influential factor. For instance, the explosion in insect diversity during the Carboniferous might well be partially attributed to the evolution of the serosa, an armour-like covering that waterproofs eggs. The success of archosaurs in the Triassic, which paved the way for the dinosaurs, is traditionally attributed to several anatomical features but might also have had something to do with parental care of eggs and nests. Lastly, the evolution of a hardened eggshell was an important factor in the success story of the birds (Howard concedes a big intellectual debt to Tim Birkhead’s The Most Perfect Thing when discussing birds and their eggs).

“Familiar as [the book’s] framework might be for readers of popular evolutionary history books, it is the subject matter that is engrossing; eggs really have been a neglected topic so far.”

Other aspects evolved in tandem with eggs, and Howard touches on sexual reproduction (a costly endeavour that nevertheless has some critical advantages), sperm, a bewildering assortment of male genitalia that deliver sperm near eggs before the female wraps the egg in an impenetrable shell, and the placenta in those organisms that develop their egg cells internally. Especially that last organ, the placenta, is a bizarre evolutionary invention when you consider it. Embryos invade maternal tissue to aggressively obtain resources needed for growth, while mothers try to balance between providing for their developing offspring and somewhat inhibiting their demands. The real kicker in this story? The protein that allows maternal and placental cells to fuse originated in retroviruses.

One thing I noticed is that Howard leaves no opportunity unused to remind you that evolution proceeds without a grand plan. Early bombardments of the planet by space debris, “without any thought or forward planning, delivered the precursors for life” (p. 4). The arrival of invertebrates on land “had nothing to do with bravery or pioneering spirit or anything like that. Rather it was the stacking up of numbers, of trials, over thousands or millions of years” (p. 48). The arms race in birds between hosts and brood parasites such as cuckoos can result in beautifully patterned eggs “without any opinion or intelligence or any artistic nous of any sort” (p. 175). In a book for a general audience, it never hurts to remind readers of this.

Overall, Howard’s writing resorts to the occasional linguistic flourish but steers clear of both excessive humour and highly crafted creative writing. Instead, Infinite Life primarily relies on delivering interesting subject matter. Adding eggs to the mix makes for a fascinating retelling of the evolutionary history of life.

Disclosure: The publisher provided a review copy of this book. The opinion expressed here is my own, however.

Other recommended books mentioned in this review:

__________________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________

Hello. Pretty much all that this book contains is new to me. Thanks for an astute review. Neil S.

LikeLike